When the enormous sheet of bedrock came creeping in over the Precambrian basement rock in Hordaland, at a speed of perhaps a few centimetres per year, it had already completed a trip from the west or northwest of several tens of kilometres or more. The reshuffling of the crust is due to the strong forces that pushed Norway and Greenland together: the Caledonian mountain building event.

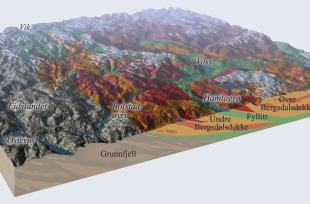

The lowermost of these thrust sheets, consisting of the Lower and Upper Bergsdal complex, is well preserved in the Bergdal area and further toward Kvamskogen and Vossfjella. It was professor Anders Kvale who named these thrust sheets and who made Bergsdalen internationally famous among a generation of geologists. Kvale argued that the sheet had moved toward the east, away from the collision zone. This theory is still widely accepted. Later research on the Bergsdal thrust sheet has nonetheless revealed that the transport story is more complicated than Kvale thought. It is now believed that the sheet wandered westward again, after the easterly transport was completed. The return trip occurred after the continental collision was over and the power of the collision had ebbed out.

The counter effect of the first movement can be compared to what happens when a large toboggan gets shoved up a snowy hill. When the pushing force is removed, the toboggan will slide back, until it gets stuck in the snow. When the Bergsdal thrust sheet slid back west, the entire layer of rock got tilted slightly toward the west or northwest, in the direction it slid. Just after the thrust sheet got stuck in the "snow", the underlying layer of rock became rotated, such that it now tilts toward the southeast.