With a herring seine they were better off

There is reason to believe that herring bays belonging to individual farms have been tended since time immemorial. In land leases there are examples that the landowner, even when he lived in Bergen, owned a majority in the herring seine, and the tenant farmer owned the rest. It was the tenant's duty to keep trespassers off the property, and to report it when herring was caught. Regular herring bays were taxed a few shillings, and they were also included in the land rent. The rule was that those who owned a herring bay also owned the seine. But there were, of course, other seines as well. The herring seine often formed the basis for a higher standard of living at individual farms.

New and old in the same seine

Usually there were several owners of a seine. Each owner had his marked section that he maintained. Thus there were new and old seine parts, one after the other. The disadvantage was that the seine was as good as the owner, and this led to conflict. If the seine was damaged, each took care of his own damage. The income was divided according to ownership.

A seine business often consisted of a big seine, an auxiliary seine, and some enclosure nets. Some owners had young coalfish seines as well, with a mesh size that could be used in enclosure nets. A seine boat belonged in the business, and a boat for pulling in the net. The new Hardanger seine boat from the Buskøybruket cost NOK 120 in 1904.

Made their own barrels

There could be 15-16 people on one seine. Maids always came along. Two young boys counted as one when they were 13-14 years old. The old man on the farm was there, his wife, too, if she could. The servants' share was taken by the master. Half the profit went to the owners of the seine and half to the others, and the foreman had the same share as the others. It was customary to pay a share to the one who reported the herring and there was a catch.

Girls and young boys salted in the sea warehouses, or onboard vessels that speculators sent from Bergen. The price for empty barrels could be NOK 3, but deft people bought prepared sticks and made their own barrels.

Heavy work in the seine rocks

Part of the older seines, at least, were homemade of hemp. Cotton was also used. If the seines stayed in the water too long, or lay wet in the boat, they were damaged. Therefore they were taken ashore to be cleaned and dried. It took a whole morning to clean a closing net. Flat, smooth rocks near the water were used for drying, where sun and wind could do the job. The seines were first pulled ashore and into a stack. Then one man walked after the other at intervals of 2-3 metres, and with the low part of the seine over their shoulders, up the rock as far as there was room. There the seine lay with the wooden float closest to the sea.

Fishing bays and seine rocks history

There are still clear marks in the rocks that were used for drying seines. Near the best-known fishing places, there were several rocks in use for drying seines. At Tverangspollen, Nothella was a suitable place, and so was Skoraberget near Stølen. Kalvikneset was used for the young coalfish seines. Farms that fished salmon dried their salmon seines in the same way. The stones were taken off the seine, except on the smaller nets. Unevenness in the rocks was picked off carefully with a chisel, an eternal process!

At several farms they began to build wooden racks to dry their equipment on. Today the summer herring seines and the racks are history. But the rocks remain if they are left untouched.

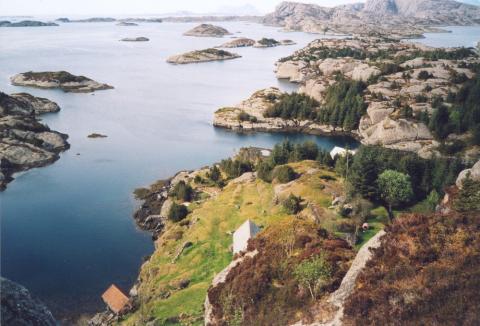

From the mountain above Stokkevåg, with a view toward the north, it is possible to see the two herring bays of the farm. To some extent the farmer could keep an eye on both bays at the same time, by sitting down on a rock north of the house. In addition to these bays, there was a fair number of good herring and mackerel coves belonging to the property.<br />

The other farm at Stokkevåg, Solheim, is situated at the end of the bay to the right, and is not included in the picture.