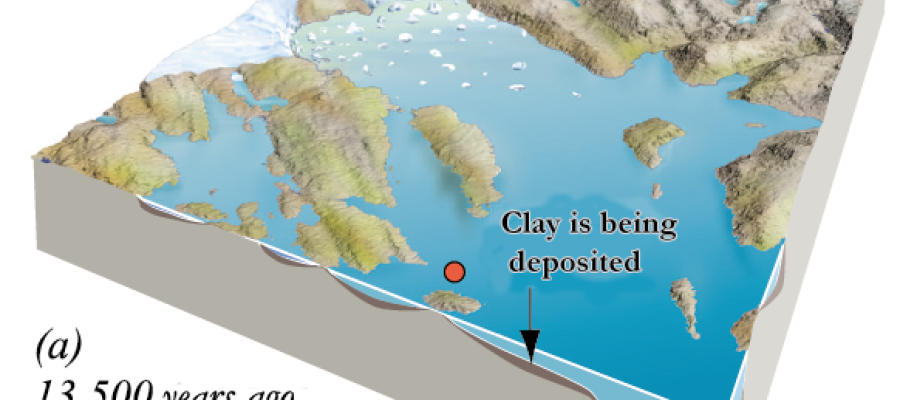

When the glacier calved back into Harganger Fjord about 14,000 years ago, the ice edge stopped a distance inside of Ølve. The river that runs out into the fjord under the glacier carried with it meltwater containing big amounts of clay, that was deposited on the sea floor just outside. Since the sea level then was about 75 metres higher than today, the clay was laid down on the fjord floor and what now is the flat area north of Ølveshovda and northwestward toward Håvik, which then lay under water. Several types of shelled organisms lived in this clay, and bits of them are dated to about 13,300 years old.

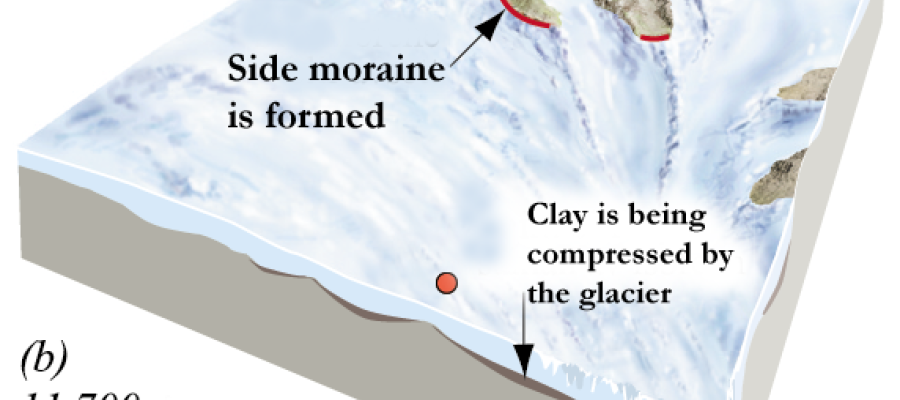

Then came a colder period (the Younger Dryas) that caused the glaciers to grow again. Hardangerfjord glacier grew out over the clay at Ølve and out to Halsnøy Island and Huglo and left an end moraine there. The height of the side moraines at Rodendalsida show that about 400-500 metres of ice lay on top of the clay at Ølve. Why didn't the glacier manage to remove the soft clay, when it didn't have any problem tearing loose large bits of rock from the mountain? The clay mass is comprised of tiny flakes with water-filled pores between them. When the glacier pressed the clay together, the pressure in the pores increased, such that the glacier didn't carve so much, but instead just glided forward over the clay, almost like water planing.

After the glacier in Hardanger Fjord had melted again, the calving wen so fast that there wasn't time to deposit much clay at Ølve. The land began to rise, and the clay surfaces were a bit washed out along the strand, but since they were so compact, most remained in place.