Railway to Flåm

In 1883 Stortinget decided to extend the Bergen Railway from Voss up the valley of Raundalen to Taugevatn on the high mountain plateau between Myrdal and Finse. The idea to construct a railway line down to Flåm was put forward in a county council session in 1885. The county politicians thought it necessary for the industry and business interests in Sogn to open up to new markets. The situation was that people from western Norway to a much too high degree competed on the Bergen market. A private railway line between Voss and Gudbangen was also taken up for consideration. In 1885 engineer Hopstock applied for a concession to build a line between Voss and Gudvangen and invited people to take out shares. The county council was positive to the idea, but nothing came out of it. Flåm was looked upon as a better alternative which would lead to faster transport to Oslo, compared to a railway line to Gudvangen.

The main purpose of the Flåm Railway was to transport goods. The transport of goods has varied from one year to another. During the development of the aluminium plant at Årdal in the Second World War and up to 1948, substantial quantities of goods were transported on the Flåm Railway. The railway also carried post until 1977 when the transportation of post was taken over by cars. In the 1970s 5 tonnes of post was transported every day on the Flåm Railway. The transportation of goods to and from Sogn was relatively stable until the mid-1960s with goods ranging from railway sleepers to fruit for the markets of Bergen and Oslo. From 1973 the Norwegian State Railways got competition from the newly established company "Linjegods" that soon took over most of the ordinary goods shipments. However, in the 1980s the hydroelectric development in Aurland meant that the goods transportation on the Flåm Railway was kept up. At the same time the construction and development of the trunk road between Bergen and Oslo implied substantial goods shipments on the Flåm Railway.

The first railway plans

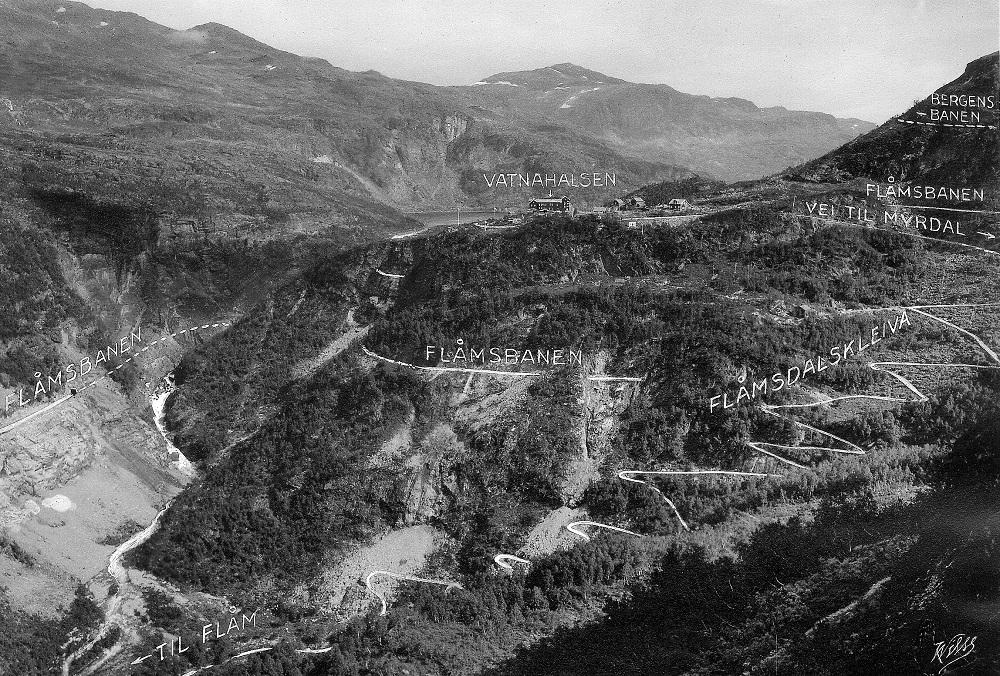

A number of alternatives were put forward as to what type of railway that could be built in 1893. One alternative was a combined adhesion rail (standard railway) and rack-railway for narrow gauge (1067mm). The rack-railway principle (cable railway) would be used for the line between Kårdal and Myrdal as they thought it would be too steep for a normal railway. The cost estimate was NOK 3.3 million. In 1905 Stortinget allocated money to find out whether it was feasible to use an electrically powered cable and road line (tram) on this section of the line. The tram would run along the road, and the cable railway would be used on the steepest part up to Myrdal. This alternative was estimated to cost NOK 800,000. This solution, however, would be highly unsuitable in the winter months. The discussion of the various alternatives was thorough.

The county council chooses railway to Flåm

In 1904 the county council appointed a railway committee which the following year presented a report on a railway connection between the Bergen Railway and the Sognefjord. In addition to the Flåm alternative, Gudvangen-Voss and Vik-Voss were still candidates. In western Sogn the parliamentary member Lasse Trædal advocated a western line - the so-called Trædal line - between Brekke and Bolstad. The railway committee decided on the line between Myrdal and Flåm. They also supported the tram alternative, using the argument that it would then be possible to consider other alternatives when they saw how much traffic there would be. In 1909 Stortinget decided a new National Railway Plan. This plan also included the Flåm Railway, but for a long time it was uncertain when the railway line would be built as it was not on a priority list with other railway stretches in the country.

Opposition from the municipalities

Stortinget put off the final decision on the Flåm Railway. One reason for the long planning process was that they had to decide on what railway alternative to use. In the county of Sogn og Fjordane many people were afraid that the railway would be so expensive that there could be problems with getting hold of the district allocations. The railway was to be financed with 15% district allocation which would be split between the county and the municipalities along the Sognefjord. Aurland would have to pay most; besides, the municipality would also have to cede the land needed for railway line for free. Only the municipality of Luster allocated the sum put forward by the railway committee. The other municipalities were dragging their feet. The municipalities were far from enthusiastic because they thought that the railway line would not be satisfactory, and other line alternatives were still lurking in the background. Aurland was in fact the municipality with the strongest opposition to the whole project.

Support for the Flåm Railway in 1915

Only in 1915 were most municipalities more or less agreed to support the Flåm Railway, but on the condition that a standard gauge was used. The cost estimate had now escalated to NOK 5.5 million. The municipality of Vik had their own railway plans and refused to pay their share. The other municipalities (Jostedal, Årdal, Luster, Hafslo, Sogndal, Leikanger and Aurland) then decided to cover Vik's share of the cost. In 1916 Stortinget decided to go in for an adhesion alternative with standard gauge (1435 mm).

The Public Roads Administration against the Flåm Railway

In 1923 came the final decision on the Flåm Railway. Nevertheless, there was still opposition to the project. In a speech in 1923, the county governor Christensen said that even after Stortinget had made a decision three times, there were still vehement attacks against the Flåm alternative. A case in point was the Public Roads Administration that did not support the plans of a railway line down to the Sognefjord. They preferred a road to be built from Voss to Gudvangen. In their opinion, the car traffic could compete with the railway in terms of transport capability. In 1927 the chief administrator of Norwegian Public Roads went so far as to present his plans to the county council. These plans meant that NOK 2.4 million would be spent on car roads in the valley of Flåmsdalen and from Gudvangen to Voss, in addition to an allocation of NOK 5 million for other roads in the county. His condition for allocating these means for roads was that the plans of a Flåm Railway were scrapped. His plans were firmly rejected by the county council.

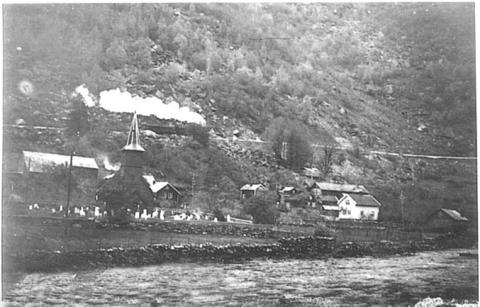

This picture shows the Flåm station in the 1960s. There were discussions going on about closing down the line. In 1998 a new company, Flåm Development Ltd., was established with the municipality of Aurland as one of the partners. The Norwegian State Railways (NSB) still has operational responsibility. The Flåm Railway is today mainly a tourist line and constitutes one of the major tourist attractions in Norway. In 1920 the number of passengers was stipulated at 22.000 annually, but this estimate proved to be too low. In the 1960s and 70s about 115.000 passengers used the Flåm Railway every year. Since the 1990s, this has changed dramatically, and in 2004 there were 459.144 passengers. The result is that the tourist business in Flåm flourishes.

Frequent attempts at slowing down the process

To a certain extent the board of directors of the Norwegian State Railways was also against the Flåm Railway. According to them, the planned line for the railway could be used as a road, and some of the money thus saved could be used to establish a bus service between Vadheim and Sandane. This was also rejected by the county council. In the Norwegian Parliament (Stortinget) proposals were put forward to offer compensation in the form of road allocations if the county was willing to give up the Flåm Railway, but nothing came out of it. In 1940 the railway could finally be taken into use. The total cost of the project was NOK 26 million.