Slates and slabs from Voss decorate the roofs in the villages and surrounding district. It has been like this for several hundreds of years, also long before the Voss railway was built, even though the quote from the book on the Voss slates makes it sound as though the whole thing started then. But the railway opened up the Bergen market, and with that also eventually the world beyond. Other countries had long had their eyes on the stone. Both Switzerland, Germany and Japan are buyers of Voss slate.

The slates are quarried from the so-called Upper Bergdal Complex. The original raw materials for the rock type were sand with a little clay. The sandstone, which was deposited more than 1.3 billion years ago, was heated, compressed and flattened during the Caledonian mountain-building event. Not only was it torn loose from the bedrock somewhere to the west and transported eastward as a thrust sheet, it was also run over by billions of tonnes of other bedrock - additional thrust sheets - that also were shoved eastward during the collision with Greenland more than 400 million years ago.

Such movements leave their mark: The quartz mineral, which originally had been round, got pressed into elongated grains, while grains of clay got transformed into mica minerals. All of the elongated minerals lay in the same direction. It is the combination of the mineral composition in the sand and the later movements of the earth that have given it its good splitting quality.

The quartzite slate lies like a layer over, and partly within, the phyllite. Glaciers and later the Strandaelvi river have carved down through the layers of slate, so that this quartzite slate is now exposed on the valley sides. The slate layer thus forms a V-form around the north end of Lake Lønavatnet. The quarries are lined up both on the Lønahorg side and, above all, at Norheim on the east side of the valley, where there are operating quarries in the area.

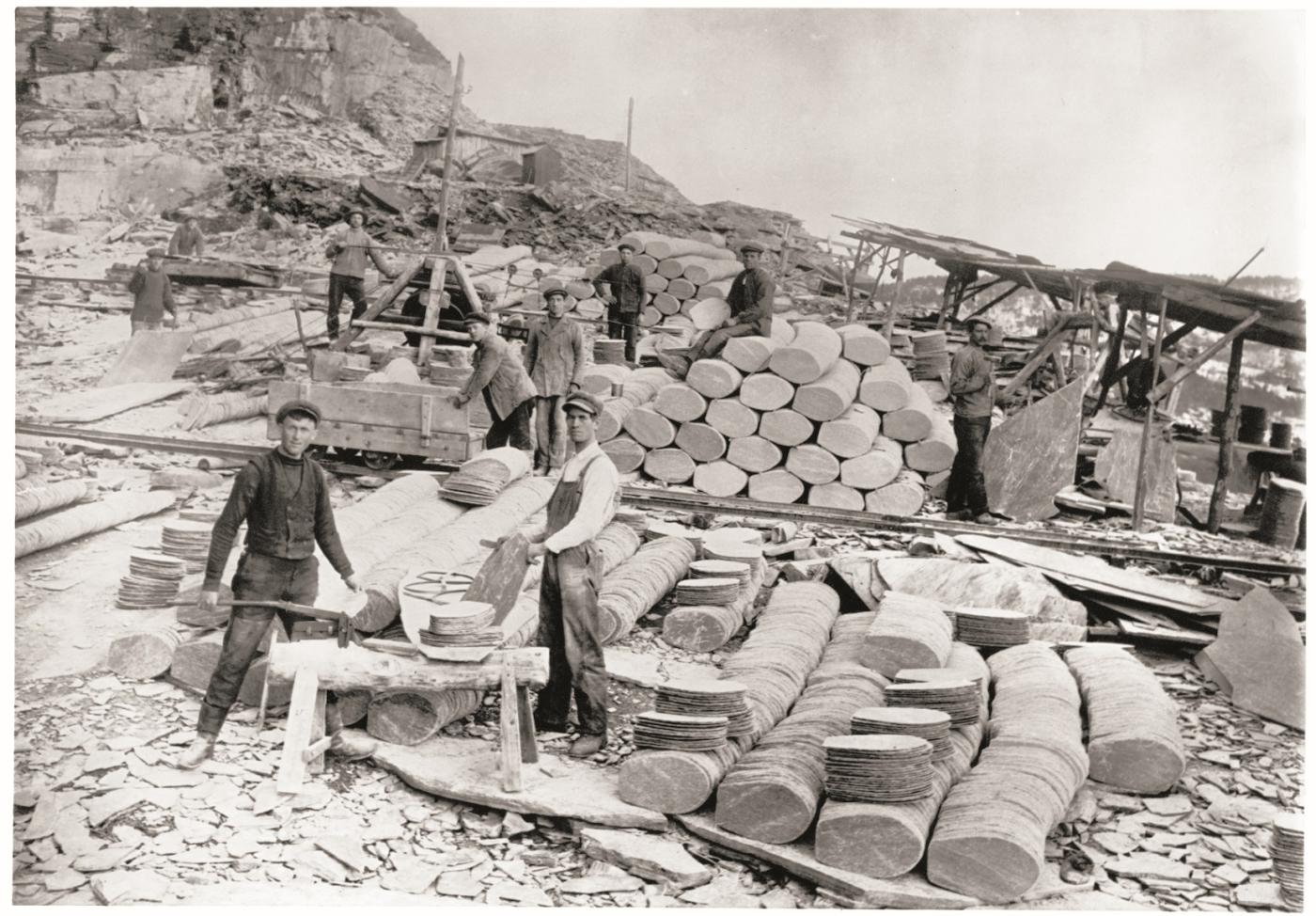

The slate varies in colour and hardness, and has been given local names by "hellebergskarane" (the "Rock slab fellows"). The hard varieties are the most difficult to work with, but they give more solid slabs. The good slate is found in layers of several metres thickness, separated by so-called "throw-away" stone. The slate has a lined- or stem structure which is related to the direction of the movements during the over-thrusting of the thrust sheets. This structure must lie parallel to the length of the roof tiles, otherwise they will be too weak.